Tucked into the flap of The Sphynx, my mother’s high school yearbook from 1949, a folded note falls out. It begins Dearest Marvin, an old love letter that feels like a find, a message from beyond the crematorium, a hidden bit of my mother’s life. There is so much I didn’t know, may never know, but here is her voice at 17, penciled onto a piece of yellowed notebook paper from 70 years ago.

The letter was lost, or forgotten, a chance find when I noticed the outer binding separated on two sides to reveal a hidden pocket. I’ve been going through my mother’s stuff with renewed interest since she died. When she was alive, her manic meanderings about people I didn’t know didn’t interest me, and I was impatient with her continual complaints. I was interested in her past, but I could rarely get a cohesive answer when I asked a question. I wanted to know about her life with my father before their divorce, and what led to her “nervous breakdowns.”

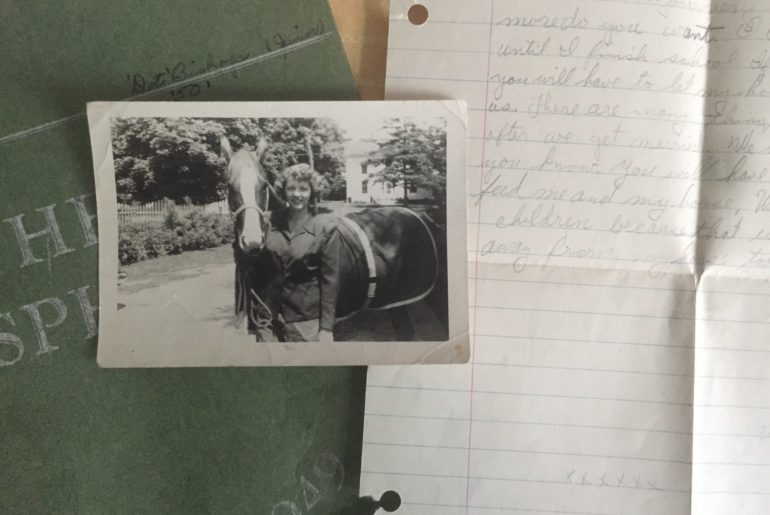

My mother talked quite a bit about her horses, a love we shared in my early years. She could remember their birthdays and the dates of their deaths. She also talked about Jack, a high school boyfriend. The last time I saw her still coherent, I showed her some pictures I’d gone through. When I asked about one, she sat up in her hospice bed, pointed and shouted, “That’s Jack! I should’ve married him.” At 86, a heart still pines for that first love.

I had heard of Jack, and why she hadn’t married him. He had a sister with Down’s syndrome, not that they called it that then. My mother was afraid she would have a “discombobulated” child if they married. Yet after we were all grown, she became a caretaker for children and adults with special needs, exhibiting a soft patience I’d rarely seen. Regret’s after-affect?

After turning down Jack, she married Walt, my father. I never heard about Marvin, and it seems he never got this letter. Maybe, like me, my mother was good at hiding things, and not so good at remembering where she hid them. I once hid my good scissors from my family who used them to cut paper. I couldn’t find them for a year. This hide-and-seek fate is my best guess on what happened with the lost love note that begins:

Dearest Marvin,

I love you very much. What more do you want. I can’t marry you until I finish school. If I marry you you will have to let my horse sleep with us. There are many things to think about after we get married. We can’t live on love you know. You will have to get a job to feed me and my horse. We can’t have any children because that would keep me away from my horse too much.

all My love,

Dorothy

xxxxxx

I knew the mother who loved horses and had five children; none of us kept her from her horses. I didn’t know the girl who tucked love letters away for safekeeping. The problem with being children is we never know our mothers as children, as young adults with concerns and lives beyond our own petulant demands on them.

I spent most of my adult years wishing my mother were different, that she could focus and listen, wishing we could have intelligent discussions, and I missed letting her be who she was, loving her manic mind anyway. This is the loss I feel now, the opportunity to see beyond my own needs, the one I don’t want to pass on with my own three daughters, or sons.

Now that she’s gone, now that I’m a motherless child in this world, I realize how much my mother has to teach me.

Comments are closed.